Data science, and numerical computing, in general, has a problem: the deep linear algebra libraries deal with pure numbers in vectors and matrices, but in the real world there is always metadata attached to those structures that needs to be carried along through the computational pipeline. Rows and columns have information attached to them–names, typically–that has to be accounted for even as we do things like remove rows or swap data around to make certain computations more tractable.

Over the past 20 years, most scientists who deal with numerics have struggled with this problem, and hacked up some kind of mostly-adequate solution for specific problems. In my own work in genomics, where data sets typically have tens of thousands of columns (each one representing a gene) and a few dozen rows (each one representing a tissue sample), dimensionality reduction is always a critical focus, and keeping the right gene names attached to the right columns at various stages of analysis while stripping out irrelevant ones was always a challenging and error-prone process.

That is, until I discovered R and learned about the miracle that is the DataFrame, which is an annotated 2D data structure that does all the metadata book-keeping for you.

Pandas DataFrame

The DataFrame is one of the things that used to really differentiate R from Python as a data analysis language, but thanks to Pandas that is no longer the case. The Pandas DataFrame class gives you a set of tools to manage metadata without even thinking about it. While I’m not going to dig into anything like the full range of Pandas capabilities in this post, they are well worth looking into: http://pandas.pydata.org/pandas-docs/stable/

Features like missing data estimation, adding and deleting columns and rows, and handling time series with realistic issues (missing data, unequal spacing, etc) all help with the areas that take up the majority of a data analyst’s time.

To show a few of the capabilities of Pandas DataFrames I’m going to walk through a simple example that looks at stock picking from a reasonably large subset of the S&P 500 over the past six or seven years. I happened to have the data lying around in a few hundred CSV files that include daily adjusted close figures, as well as a bunch of stuff I don’t care about for this example. To get the data into a single data frame requires we read each file, rename the last column from “Adj Close” to the stock’s symbol, and then append the last column to an existing DataFrame:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import matplotlib

import pandas as pd

matplotlib.style.use('ggplot')

# read the data in and construct a dataframe with dates as row labels

# and ticker symbols as column labels

for strRoot, lstDir, lstFiles in os.walk("sp500"):

for strFile in lstFiles:

if not strFile.endswith(".dat"):

continue

stock = pd.read_csv(os.path.join(strRoot, strFile), index_col=0)

strName = strFile.split('.')[0]

try:

data = pd.concat([data, stock['Adj Close']], 1)

data.rename(columns = {'Adj Close': strName}, inplace=True)

except NameError, e:

stock.rename(columns = {'Adj Close': strName}, inplace=True)

data = stock[strName]

print data.head(2)

print data.info()

The print statements let us look at the first couple of lines of data and some metadata on the frame. Looking at the data is a critical part of any data science workflow.

The output allows a reality check, and shows how Pandas conveniently compacts large amounts of data into a useful summary:

aon dnb ter tss afl noc \

Date

2010-01-04 34.715489 73.291471 10.578442 15.567722 39.576707 42.621445

2010-01-05 34.495888 73.221140 10.617049 15.567722 40.724823 42.696418

ed pnc wba fitb ... de \

Date ...

2010-01-04 33.294581 45.778316 32.020453 8.626868 ... 47.140779

2010-01-05 32.861707 46.240292 31.762917 8.857031 ... 46.964187

hrb duk whr vfc rrd bmy \

Date

2010-01-04 17.479852 36.277232 69.636036 15.574674 14.239947 20.036926

2010-01-05 17.233005 35.678668 69.491583 15.871820 14.208596 19.724216

mro yhoo ge

Date

2010-01-04 16.149688 17.10 12.176547

2010-01-05 16.164781 17.23 12.239597

[2 rows x 409 columns]

<class 'pandas.core.frame.dataframe'="">

Index: 1843 entries, 2010-01-04 to 2017-04-28

Columns: 409 entries, aon to ge

dtypes: float64(409)

memory usage: 5.8+ MB

None

Think how often you’ve written loops to do exactly what Pandas is doing automatically here, writing out the head and tail of a couple of rows to makes sure things are basically OK. This sort of code isn’t difficult, but it’s very, very nice to not have to write it.

The loop that reads files and creates the DataFrame could probably be made simpler, but it only takes a few seconds to run and gives us what we want. One of the many nice things about Pandas is it will attempt to do something sensible in the case of incomplete data, although in that case the DataFrame would wind up with some NaN’s in it. Fortunately, Pandas makes it fairly easy to replace NaN’s with estimated values, likely in this case with a simple column-wise interpolation.

Now that we have the data, we can see if there is a simple stock-picking algorithm that will make us billionaires. There are a lot of approaches to this problem, but for the sake of simplicity I’m going to focus on a single robust estimator. Robust estimators are based on counting things or ranking things rather than cardinal values. To a robust estimator the sequences (1.2, 5.8, 100, 28) and (1, 9, 1500, 10) may well look identical, as they have the same rank ordering. For noisy data–that is to say, real data–this kind of robustness is very desirable.

On that basis, I thought it would be interesting to pick stocks by counting the days they go up. The stock market generally goes up about 2/3 of the time in bull markets (and about half the time in bear markets) so we expect that the average stock will go up about 2*1843/3.0 = 1229 days out of the 1843 days in the dataset, unless the market has some internal structure. That is, in a structureless market the price of the average stock will behave the same as the average price of stocks. In a market with structure, some stocks will go up enough to lift the market ⅔ of the time, even though most stocks may go down on any given day: the gains are not uniformly distributed across all stocks in the market.

The process of getting at this view of the market nicely illustrates some of the power of Pandas:

# take the one-day difference, throwing away the first row as it is NaN

dataDiff = data.diff()[1:]

# find out which stocks have the most up days

countPositive = dataDiff > 0

upDays = pd.DataFrame(countPositive.sum())

upDays.hist()

plt.show()

The “diff” function on Pandas DataFrame does what you would think, and it takes a “periods” argument that allows you to take more than just one-day differences. It also takes an “axis” argument that allows you to diff in different directions along the data. In our case, those aren’t needed, though.

Applying a comparison operator to a DataFrame works as shown, and it returns a new DataFrame that has boolean values depending on the outcome of the comparison.

The “sum” method on DataFrames returns a lower-dimensionality data structure (a Series, in this case) that can be used to create a new DataFrame. The fun thing is that the column labels from the original dataset are dragged along through this: sum is run down columns, which is the natural thing you would want it to do.

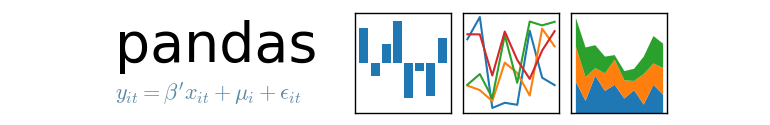

DataFrames have plotting methods that are convenience wrappers around matplotlib functions, which is why we have to call pyplot’s show() method after the call to hist() on the DataFrame, which sets up some fairly intelligent default values and generates a plot as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: admittedly not very pretty, but dead easy to generate

Curiously, the peak of the histogram is around 950 days, not 1229 as predicted above. This tells us the market has structure: stocks that go up must tend to go up more than stocks that go down, so even though the average stock only goes up half the time, the overall market goes up 2/3 of the time. This is something that could easily be checked if one wanted to take this analysis seriously. This kind of internal checking is critical to the practice of data analysis in the real world, and when people talk about “learning data science” it is this kind of thing they should be most concerned about.

Having decided to focus on stocks that go up more frequently, we can set a threshold at a nice round number like 1000 and look only at the stocks that make the cut using the fancy indexing capabilities of the loc member of the DataFrame:

print upDays.loc[upDays[0] > 1000]which identifies 16 stocks that go up more than 1000 of the 1843 days in the dataset.

But is this condition a useful predictor of anything? Simply knowing “some stocks really do go up more frequently than others” tells us nothing. Maybe it’s just randomness!

To create the most rudimentary test possible, we cut the dataset in half, looking at the first 1843/2 days and then the second 1843/2 days.

# now split data in half and see if the effect persists

nDivide = len(countPositive)/2

firstHalf = pd.DataFrame(countPositive[0:nDivide].sum())

secondHalf = pd.DataFrame(countPositive[nDivide:].sum())

# selection criterion is now > 1000/2

firstTop = firstHalf.loc[firstHalf[0] > 500]

secondTop = secondHalf.loc[secondHalf[0] > 500]

# the critical thing is how many of the stocks are in common

# between the two lists: if the test is predictive it will

# be higher than randomness would predict

intersection = firstTop.index.intersection(secondTop.index)

print intersection

print len(firstTop), len(secondTop), len(intersection)

# which means we must look at what randomness would predict

fExpect = len(firstTop)*len(secondTop)/float(nDivide)

print fExpect

When we run this code, the output gives us 7 stocks in common between the two lists and the expected value is 0.82. Because we are counting a small number of things, the appropriate null hypothesis is given by the Poisson distribution and we can reject this pretty hard: the probability of a Poisson process with a mean of 0.82 returning a result of 7 or more is 2.4E-5.

So it looks like the outcome of this analysis is broadly positive: we have found a simple method of identifying a small number of stocks with a higher-than-average probability of going up. But before we rush out to invest, it’s probably a good idea to consider additional questions like “How much did those stocks actually go up by?” The downside of a robust estimator is that it throws away information, and that may throw out the signal with the noise. In this case, we have identified stocks that go up with about the same probability as the market itself, but we have no idea if they go up by as much as the market does on average, or considerably less (or possibly more).

Furthermore, the lists of stocks found in the first and second halves of the data had lengths of 18 and 42, respectively, so if we apply this criteria to stock picking we may find ourselves with 5 or 10 modest winners and twice that number or more losers. While tools like Pandas can really help us navigate the data and focus on our analysis work rather than the book-keeping of metadata, we must always, in the end, use our judgement and (ideally) simulation to decide if the outcome of an analysis has any real-world utility. There are many other things besides metadata that come between the results of pure numerical analysis and practical value.

Title image courtesy of Michael Droettboom under Creative Commons License.